Between 2020-2021 we were unable to stage a Jocelyn Herbert Lecture due to the Covid pandemic and, instead, are grateful to Dame Harriet Walter for writing her thoughts about the role of the designer from the perspective of an actress.

Harriet Walter outside 9 Lower Mall, Hammersmith, London, with its plaque commemorating the years when it was home to George Devine. Devine, with Tony Richardson, founded the English Stage Company where, at the Royal Court Theatre, Jocelyn Herbert began work as a scene painter before designing her first production there, Eugene Ionesco’s The Chairs in May 1957. Photo credit: Guy Paul, 2021.

JOCELYN HERBERT LECTURE

A NECESSARY SURRENDER: Or an actor’s subjective view of design

In the beginning is the word. In the context of an essay about theatre design that may seem blasphemous but it usually starts with a text; a play text that we all read slightly differently inside our heads. The director feels out the overall structure of the piece, taps into the writer’s intentions. The producer makes a mental list of needs and costs. The actor reaches for the character, sounds out their words in his/her head and the designer sees the play. The thing we are all aiming at is the physical realisation of what is as yet only a blueprint. Just as a musical score is mute until the orchestra strikes up, a play text needs the whole pool of production talents to bring its meaning into physical form for the audience to share.

In fact all our disciplines overlap as we privately read. The designer delves into character, the lighting designer hears the words, and all of us in some way start to visualise the play.

Pre-rehearsal

I have just been cast. Rehearsals are a soothing distance away. I sit on the top deck of a London bus dreaming my part into existence. I look at the crowds below me. “Who might she be?’ “Does she dress like that woman there?” and “Could I ever be her?”

I lie on my bed following wherever my meandering daydreams lead. I dream in 3D. This is the best time, the freest time, when anything is possible. As I walk through my dream landscape with its filmic jump cuts, questions start to bloom around me: “What does she most hope for?” “What is her greatest fear?” “Where did she grow up?” These I can begin to answer on my own. Other questions, as in life, are none of my business; “What do other characters think of her?” “Does her husband love her?” and I look forward to testing some of them in play with other actors.

I can privately build a coherent inner life for my character. I can even start to try out the physicality that this inner life suggests to me. Is her speech fast or slow? Are her gestures calm or agitated? How does she move and walk? All answers to be instinctually inferred from the text if I am working well and if the writing is good. Less good writing needs me to pad it out and prop it up. I can develop some very strong notions about the overall meaning of the play and how my character fits into that but when rehearsals begin my ideas may be crushed by a stronger daylight of consensus. Better not to fall in love with them too early. So I put the brakes on and long for rehearsals to start.

I start to form some embryonic costume ideas. I will be able to throw some suggestions into early discussions and these stand a chance of being accepted and absorbed into the designer’s scheme, but the set is a different matter. Costumes, which may or may not come under the same designer as the set, are understood to be a subject for discussion between actor, designer and director, but the set, the style, the physical concept, the world the audience will see depicted is a done deal before I come on board and this is simply because the timescale demands that workshops start set construction a good while before rehearsals begin.

First Impressions

First day of rehearsal and the designer shows us the model. It is explained in terms that chime with the overall philosophy of the production as outlined by the director earlier in the day. We gather round like so many giants looking down on a Lilliputian world. Our previously free-roaming imagination is now literally boxed in. This is what the audience will see. This is the way the story will be told. But if some of my dreams are stamped out, others are taken further than I ever dared. Questions are asked and worries are aired. For the most part we are delighted and impressed and give the designer a round of applause. It is too late to radically alter anything anyway. We surrender, and for the most part we are happy to do so.

Remember this little box because you won’t see it again. The next time you see that matchstick staircase it will be on a life-size set at the technical rehearsal and you will be learning to run up and down it as if you had done so for years. The solid structure all around you is to be your “home” for the length of the run. You will no longer be looking at it but living in it.

Photo of model for Women Beware Women by Thomas Middleton, design by Lez Brotherston, Olivier auditorium, National Theatre 2010. Photo credit: Unknown.

I have described the usual pattern of things in the UK, but I have been lucky enough to experience some memorable exceptions to that norm. When I worked with the Russian director Yuri Lyubimov on the Almeida’s production of Dostoevsky’s The Possessed in 1985, I rubbed shoulders with a more European experience. For all its other faults Soviet Russia respected the theatre and therefore threw money at it. Lyubimov had been nurtured in that regime like a spoilt infant. He was a genius of sorts partly because he was allowed to be. When we worked with him the spoilt child had been kicked out of his home but he expected the same standards and treatment from his adoptive UK. Somehow Pierre Audi, the then artistic director of the Almeida, himself tuned in to European priorities, found the money to fund a large cast for an 8 week rehearsal period in a space where Stefanos Lazaridis’s entire set was up and running from the first day of rehearsals. Three black walls of narrow elasticised strips, which parted when we entered and snapped back immediately after, contained the action of the play. Costumes props and furniture were expedited directly from Lyubimov’s whimsical imagination to concrete existence in the rehearsal room at frightening speed. Nervous breakdowns hovered in the air above actors and stage management alike. But paradoxically, within Lyubimov’s seemingly rigid parameters there was much leeway to be found and this was largely helped by having the real performance space to practice in from Day One.

Maria the Cripple experiments with the elastic walls in rehearsals. The Possessed, adapted from Fyodor Dostoevsky by Yuri Lyubimov, design by Stefanos Lazaridis, Almeida Theatre, 1985. Photo credit: Member of the cast of The Possessed, name unknown.

Row of actors in masks with heads through the set. Each actor wore a mask and had a mask in each hand, thus tripling the size of the mob. The Possessed, adapted from Fyodor Dostoevsky by Yuri Lyubimov, design by Stefanos Lazaridis, Almeida Theatre, 1985. Photo credit: Member of the cast of The Possessed, name unknown.

The other exception was when I worked with Joint Stock Theatre Company. Founded by Bill Gaskill, Max Stafford-Clark and David Hare among others, Joint Stock developed a way of working that involved bringing together a group of people for a workshop with an aim to creating a piece of theatre. This group would include the writer, director, designer and actors who would all start from the same Page One. This meant that the design grew up around the practical needs and imaginative ideas that cropped up in rehearsal. Joint Stock was relatively well funded by an Arts Council project grant and more than any other commodity that money bought us time. Time to research and develop a piece in a 4-5 week workshop, time for the writer to then go away and write the piece up, and time for a normal period to rehearse the play. This time afforded us the luxury of growing a design organically alongside the day-to-day work and creating a space we all could happily own.

Back to the commercial norm. After that showing of the model, the designer has abandoned us to our private world of rehearsals. Reminders of the overall plan; torn out photos from reference books, the designer’s sketches might be blu-tacked to the walls around the rehearsal room. Furniture and props are being created in the workshops or will be hired nearer production time, so we work with substitute furniture and props, and a floor plan marked out in brightly coloured tape keeps us spatially aware.

Most actors love this period when, aside from the odd alert “You can’t stand there, it’s a fireplace/stairwell/river” our experimentation can wander free of walls and doors and mechanics. The work all happens behind our eyes and in our bodies. The most important transition is that of the words from the page into our brain and bloodstream. A text held in front of you acts as a shield, a safety net but at some point it becomes a frustrating hindrance. You want to run not stumble, like a kid getting rid of their bicycle training-wheels. Going “off book” is the only way to grow and own the character. You falter and stumble and embarrass yourself but with practice you crash less often. Bit by bit we drop our “shields” and build on the reflections of our characters that we can now see in one other’s eyes. It is a privileged time and a trusting time. I am reminded of Virginia Woolf’s phrase “When the walls of the mind become transparent”

Costume

At intermittent points during rehearsal we have meetings with the costume designer. Some designers make a point of watching a lot of rehearsal so they can learn more about the way we/our characters move, sound etc. Others are perhaps too busy and rely on feedback at production meetings. The earlier in the process that I am introduced to some costume drawings the better. This is where my imagined image for my character confronts the designer’s imagined image and it can be an inspiring, exciting experience or possibly a shocking or disappointing one. Some designers have the tact to represent a believable version of you, others might rather thoughtlessly depict an impossibly idealised form and you know that when you actually step into that costume you can only be a let-down.

I have worked with the full spectrum of designers from those who see you as a tailor’s dummy to fulfil their fashion fantasies, to those who share as deep an analysis of character as your own and are willing to curb their own flamboyance in favour of a more telling minimalism. This can be a glorious collaboration; two disciplines working towards a common meeting place. I may have been groping for something I couldn’t quite see while the designer has formed a strong visual idea but can’t quite nail a justification for their instincts. In discussion we hope to bridge those gaps.

Staged truth is a very selective truth. It is necessarily far more selective than film where the camera can point at a busy high street, a mediaeval castle, fly above the clouds or beneath the sea. That isn’t to say that film production designers don’t have a job- that is far from the truth, but my point is that on stage the designer needs more ingenuity and operates on a way smaller budget. Every detail needs to resonate. Nothing the audience sees is extraneous.

This applies to costume. If I wear a red dress, that red means something. Accidents are not allowed. So the designer and I make decisions together about how my character’s appearance works within the design frame. The design may be expressionistic and abstract. The whole cast may be dressed in the same style that deliberately neutralises our individualism in order to highlight some larger meaning. Our clothes may be unrelated to period or fashion or nation but a complete invention by the designer. I love the idea of stepping into these new “bodies” and seeing how they affect my movements. At this point in the process I can only speculate as to what problems might occur down the line; the weight of a headdress, or the discomfort of the shoes etc. I can shelve those worries for now.

If the costume is naturalistic we will be asking some fundamental character questions like; how does she present herself? Does she wear her heart on her sleeve or does she hide behind layers of misleading armour? How much is she invested in her appearance? Does she use fashion to intimidate or make a statement or does she just wear clothes? My character may be someone who doesn’t care what she looks like but in design terms her insouciance will be calculated. Her baggy jumper and pyjama bottoms will say something about her and how she feels that day.

In real life my own random eclecticism of dress would fox anyone trying to stereotype me but on stage I need to be more consistent. I need to be recognisable as a type even if the ultimate aim is to subvert it. This is particularly true if there is a large cast of characters and my own makes only intermittent appearances. The audience must immediately recognise me in Act V if I haven’t appeared since Act 1.

Designers vary as to how much they collaborate with actors. I have certainly experienced situations where a designer simply drapes fabrics over me and stands back to observe as though I were a painting on an easel. As I said before, for the most part I am happy to surrender to someone else’s vision as long as I can do my acting job within it.

Whether bouncing ideas back and forth, or being passively draped, the first meeting comes to an end and the designer and I go back to our separate work-places.

A couple of weeks later there is the first fitting and I know I will suffer. At this point I have to be sexist and say that nine times out of ten a female designer understands what a male designer does not and that is that we are all paranoid about our own body image. Then I can counterbalance the sexism by saying that this paranoia applies to actors and actresses alike. I have learned to quell my rising panic and remind myself of all those other first fittings that have ended up in final glory on opening night.

I take the developing design image for my character back into the rehearsal room and feed it into the work. I use a rug for a cloak, a battered straw hat to represent some beautiful headdress that is at the maker’s. If it is a period piece the women will have been wearing “practice skirts” and hopefully some shoes that “give” us our walk. The male actors will get a sense of how wide a berth they must allow us when entering a room with us. We often rehearse a period play in a corset of some kind and this contributes not only to our posture but to our gestures and behaviour. These things in turn feed back into our minds via our bodies adding to the process of becoming someone else who lived in a different time.

Like a lot of disciplines when something is done well you barely notice it and I have been known to take a good designer for granted. It is easier to illustrate the importance of a designer’s contribution by describing the times it goes wrong.

My earliest lesson was at drama school. We did a devised play based on Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress. It was our second year and we were learning about non-naturalistic forms of theatre and Pilgrim’s Progress, being allegorical in nature, was a perfect vehicle for experimentation. As a group we were encouraged to thrash out religious and moral arguments, choose which scenes of the book should be dramatised and how. Although the director had the ultimate say he allowed us a lot of leeway and it was a memorably creative time.

It has become a rather laughable drama school cliché but yes, we did study animals. And I loved it. The idea is to study the movements, breathing rhythms, physical restrictions and abilities of specific animals (trips to the zoo were frequent and we would often criss-cross with other drama school groups on similar quests). The exercise helps an actor to get out of their own physicality and imaginatively reach into a different body. Acting from the inside out means I think happy thoughts and they cause me to smile and move in a jaunty manner. Acting from the outside in involves the opposite. I smile and run around the room and the action gives me a feeling of happiness. Animal work requires acting from the outside in and then doing a bit of anthropomorphising. I watch a lizard slowly blinking on a rock. I slow down my movements and my thoughts slow down with them. I learn economy of movement and decide that this fits a certain type of character.

Our version of Pilgrim’s Progress pitted the hero Christian against a powerful Big Brother-type State (it was back in the 1970s) and I was cast as an evil agent of this state known only as The Interrogator. What animal should I be? In the zoo I had studied a camel and a panther, I had also generally studied a pigeon. I had successfully brought their properties into the rehearsal room and created a human character that behaved like them. My camel was snooty, my panther was a paranoid pacer, my pigeon a muttering old lady on the bus. None of these would work as The Interrogator. So I came up with the idea that she was a praying mantis. Sinisterly still, usually invisible but ever-watchful with her 180 degree lamp-like eyes. The director encouraged this and stage management found me a thin black pole about 3 meters long which I held at an angle with my body sort of slantingly perched on it, freezing all movement until I needed to pounce on Christian with a question. It was all going extremely well until……The technical rehearsal. The designer presented me with a square grey jacket, a square grey skirt and some military boots. She had seen The Interrogator as a stocky Soviet Rosa Kleb and my stick insect snapped, jack-booted out of existence. I had no choice but to wear that costume and as my mentally visualised “long” was forced into a physically actual “square” my entire character crumbled. I lost her.

Of course in the professional theatre this wouldn’t happen because we would see drawings and have discussions long before the dress rehearsal but this negative lesson has stayed with me forever to define something of the relationship between costume and performance.

Fortunately the more senior I became in the profession the sooner I was let in on some of the production ideas and in some cases this meant I could influence some aspects of the design before they were finalised. Almost every instance I can think of where I chipped in my pennyworth had to do with the feminist point of view. To give an example; in 1999 when I heard that director Greg Doran and the designer Stephen Brimson Lewis were going to set Macbeth in modern dress, I resisted the idea for my Lady Macbeth on the grounds that so much of the relationship between Macbeth and his Lady was to do with her dependence on him for any status in life. Her ambitions were for him not for herself because there could be no path for her independent from his. Setting the play in a world of short skirts would necessarily bring up questions as to why Lady M didn’t aim at ruling the country herself? Why operate through her husband? Even if these questions remained subliminal in the audience’s mind they would nevertheless undermine any understanding of the motivation of a childless Jacobean woman desperately clinging on to survival via her husband’s last grasp for power. I don’t think I put my arguments quite like that at the time as they were only half-formed before we started the work, but I did get the concession of some long dresses that were featureless enough to be timeless.

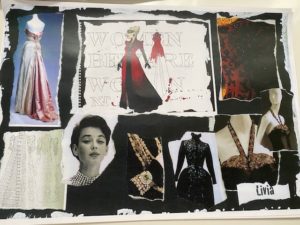

An example of the opposite experience was when I did Middleton’s Women Beware Women at the National Theatre. In this instance I joined later in the process and had never worked with the director, Marianne Elliott, before. In our first meeting we were sounding one another out and I waxed enthusiastic about the rich Jacobean text and how to me it was redolent of 17th century city smells, blood, danger and disease. Marianne cut me short by announcing that the production was to be set in 1950s Rome, a hard-edged sophisticated Fellini-esque landscape created by designer Lez Brotherston, in which my character Livia would owe a whole lot more to Sciaparelli than van Dyck.

I went with it, though once again I felt that the relatively modern context tilted things unhelpfully for my character. In Jacobean times to be a wealthy widow was the highest vantage point a woman could reach. Put the character in post-war Italy and the way she uses her power becomes straightforward appalling, blatantly grooming young vulnerable women to be dished up to rapacious men. To play a purely evil woman never interests me. I need to find a human motive. I had figured that in Livia’s book she is justified in her manipulations. She is giving the young women the advantage of her own wisdom in order to steer them along a similar path to the one that helped her survive. It is a path of plotting and poison that although not pleasant in any era is more understandable in the kill-or-be-killed 17th Century than in 20th Century Rome.

However Italy in the 1950s was still a pre-feminist culture so the play worked extremely well and I surrendered my principles to the sheer pleasure of wearing glamorous frocks on a spectacular set.

Lez Brotherston’s costume ideas for Women Beware Women by Thomas Middleton, Olivier auditorium, National Theatre, 2010. Photo credit: Unknown.

The model becomes the set, Women Beware Women by Thomas Middleton, design by Lez Brotherston, Oliver auditorium, National Theatre, 2010. Photo credit: Simon Annand.

The Merry Widow. Women Beware Women by Thomas Middleton, design by Lez Brotherston, Oliver auditorium, National Theatre, 2010. Harriet Walter as the Merry Widow, with Guardiano played by Andrew Woodall. Photo credit: Simon Annand.

But let’s wind back to…

The Technical Rehearsal

A time for keeping your nerve. You have said goodbye to the comforting rehearsal room that has been your home for several weeks. You will have done your last run- through there and very possibly had a first reaction from a small invited audience (usually theatre staff). Especially if it is a new play, it is thrilling to get your first feedback, that first laugh, or other indications that things have worked- maybe even tears or a gasp of shock.

In the actor’s mind that last plain-clothes run-through in the rehearsal room is the most direct uncluttered rendering of the play that will ever happen. Costumes, set, sound, lights and a real audience will lift it on to another plane but there is also something lost, a raw innocence that you try in vain to recapture during the run and hold precariously in your memory as a guide.

You rock up at the theatre early on the first technical day. The technical rehearsal is all about the mechanics of the production, music cues and lighting levels, props, costumes and carpentry. The actor can and should leave the acting behind and focus on how do I get through that door? How do I do that impossibly quick costume change? Can we please move that vase? My shoes hurt. Can they be stretched etc etc etc.

You are as likely to be thrilled by the very real set as alarmed by it. You screech with delight as you and your fellow actors parade in newly revealed costumes, but oh dear the guy I am supposed to fancy has got a terrible wig and the passion that had been easy to act before will now be a struggle. How superficial am I?

Then there is the set itself. Take for example A Midsummer Night’s Dream which I did very early on in my career at the RSC. It was designed by the late very brilliant Maria Bjornson. The concept was that of an attic of Victorian toys that come to life. The fairies were puppets, and we lovers were dressed in chocolate-box dresses with huge crinolines that came into comic effect when our Victorian decorum was (literally) stripped off us in the big showdown scene at the end of Act III.

GL2/2/1981/MND1 neg E4627: William Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream performed at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, 1981. This production was directed by Ron Daniels and designed by Maria Bjornson.

Juliet Stevenson as a toy Titania in A Midsummer Night’s Dream by William Shakespeare, design by Maria Bjornson, Royal Shakespeare Company 1981. Photo credit: Joe Cocks, by kind permission of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust.

Technical rehearsals last for days and there is time for us to go into the auditorium and look at the picture we are going to slot into. This is actually a vital part of the process. To go up into the gallery and see how far away you will look and how much you will need to project and lift your face into the light. You can sit back in the stalls and marvel at the magical special effects, the shafts of light cutting through a dawn mist in the forest etc BUT when you get back up on stage to walk through your own scene, the leafy forest floor conjured for the audience is for you a prosaic set of wooden planks with a trap door. The woods we vanish into are propped up wooden wings. This is one of the biggest lessons for an actor to learn…The magic is not for us but for them. My business is to transport the audience into another time and place while remaining acutely tuned to the here and now.

Performing in the Space

So this is it. This is to be my home for the next few months or more.

Some writers rigidly lay out their own design vision : “A kitchen table takes up most of the acting area. Upstage right there is a washing machine with piles of dirty laundry in a basket on the floor next to it.” etc.

This must be very constraining for a designer, but paradoxically it can be liberating for an actor to be tethered to a “real” room with real carpets and sofas and bookshelves (albeit set at a jaunty angle and lacking a fourth wall). It can leave us free to focus on our character. More abstract designs or non-domestic settings require more from the actors. We have to help create the place.

‘You can tell from my unfitted costume that this is a technical rehearsal. HW. ‘The Royal Family by Edna Ferber and George S. Kaufman, design Anthony Ward, Haymarket Theatre, London, 2001. Photo credit: Robert Petkoff.

Many writers leave much to the imagination. This is certainly true of Shakespeare. On first reading his plays I hear them rather than see any scenes. Vague indications like “The King’s palace” or “A wood near Athens” leave us free to hold the mirror up to our contemporary world with Shakespeare’s blessing. He of all people knew the power of the imagination and invoked the audience to help create the battle of Agincourt in the “wooden ‘O’” of the Globe theatre.

Think when we talk of horses that you see them

Planting their hooves in the receiving earth

For ‘tis your thoughts that now must deck our kings…..(Chorus. Henry V)

However minimal, a design is always very deliberately thought through. In other words even a non-design is a design decision. By moving believably within an invented environment the actors reinforce the “truth” of the designed world for the audience. If an actor resists a design they will only look stupid and not be believed. Even if you hate it you kind of have to go with it because ours is not to judge the effect. We can be terribly wrong in our judgments. The nature of our role is subjective and should remain so.

As I said earlier, theatre can’t do what film can do, driving through streets or flying over vast battlefields. Nor can it flit from battlefield to bedroom in the blink of an eye that cinema editing can achieve. A theatre designer shares responsibility for the rhythm of a play. Unless they incorporate mechanisms for speedy scene changes we will curse them. They may be off to Bayreuth or somewhere for their next job, but we plodders who work on the set 8 times a week have to live with the consequences of laborious scene changes; audience fidgeting, suspension of disbelief destroyed, actors’ energy sinking into the floorboards

A good designer will combine poetry and practicality. They create everything the audience sees- and does not see. A good designer places the tip of an iceberg on stage and the audience goes away remembering the whole submerged mass as if they had seen it with their own eyes.

Actors can help that too. Another lesson from drama school; I’m watching a production of Chekhov’s Three Sisters. It is a final show by the overseas students. They were mostly Americans and I have to say they were more physically relaxed than we Brits were. One of the actors seemed so completely to inhabit his costume and seemed so totally at home on the stage that I remember “seeing” the rest of the house that he exited into or entered from. There was obviously only one room on stage surrounded by narrow wings but that actor transported me to a world beyond that so effectively that I never forgot it. I realised that great actors can carry a world in their body and make other people see what is not there.

I have to talk a little about directing because the illusion of theatre is created by teamwork. The job of each team overlaps as well as having distinct areas of responsibility. Directors vary hugely in their attitude to design. Some are cerebral and would rather there were no design at all. They love the purity and directness of the actors’ communication through the text. Others treat actors like objects to be shifted around in the space like those little cardboard figures in Victorian toy theatres, and there is every type of director in between.

There are directors who mess with your head, invading the territory that is yours; your character’s motivations, their feelings and thoughts. I don’t want you in my head. I want my director to be the mediator between me and the audience. I need their outside eye to remain outside. If a director ever says to me “remember she is afraid of her father because…” I have to be restrained. The point is that I know that bit and if it isn’t coming across, I need you to help me show it. I don’t want to overact or demonstrate either and if I am having to do that it may be because I am in the wrong place on stage.

Lindy Davies, the Australian director, talks about the actor’s kinetic intelligence. She would allow us to find the position on stage that best supported our purpose at any one time. Each actor, at least in rehearsal, was allowed to explore all the spatial dynamics available, even when two actors’ paths collided (actually they seldom did). I learned that one’s reason to move, to sit, to stand, to lie on the floor, owed as much to instinctive emotions as to practical necessity. If the latter were all that was needed, if I have to tell another character something and they are right next to me why move at all? I can stay put until I need to fetch a glass of water or grab a gun or exit the room but that would make for pretty dull staging. So I move upstage, at an angle, cross to the window, stare out of it, creep up behind you because I want to avoid you, impress you, scare you, surprise you. Left to my own devices I might either get rooted dully to the spot or be distractingly busy. I need the director to guide me, to help me tell the story within the space. I need a director that understands that design of a space is not just illustration, or conceptual context but also a platform for performance.

Phyllida Lloyd has a wonderful kinetic and spatial intelligence. I worked with her a lot in 3-sided or 4-sided spaces which require a self-effacing designer to clear the view across the area. Furniture is minimal. Chairs are low-backed. Scenes are created with light shafts and floor cloths, projections on back walls. Phyllida’s staging within these spaces frequently made use of the diagonal. We would play major scenes standing on opposite corners of the space. Not only does it make for dynamic relationships between people but it also ensures that, with an audience all round us, everyone is seen by someone all of the time. Those who can’t see my face, for instance, can see the faces of other actors reacting to me. They can also read something into my posture from the back.

I could trust Phyllida to place me where my acting could be “read” by the audience. One example stands out. We were doing Mary Stuart at the Donmar Theatre where there is a main central seating block and two smaller blocks on either side and upstairs seating wrapping around the same area. I was playing Elizabeth I in a council meeting with her advisors, all men. I hear each man out as they present their arguments as to how to deal with Mary. Their political strategies directly oppose one another. Some favour Mary, some hate her. The final buck stops with Elizabeth and the decision is agonising. Anthony Ward had created a sombre minimalist set. A black-bricked back wall which could serve as prison or palace. Only a few sticks of furniture. A narrow iron bed for Mary’s cell and a large rectangular box would serve as my throne.

Early on in rehearsals of this Privy Council meeting, Phyllida was trying out various positions for my throne in relation to my councillors and, ever the experimenter, suggested I sit with my back to the audience with my councillors lined up on a bench against the back wall. We rehearsed that way week after week and privately I was hoping (and expecting) her to eventually swap things round or at least set me on a diagonal line with my courtiers. They did most of the talking so I understood they needed to face outwards but what of me? I had few words in the scene so surely the audience should be given access to my oh-so-expressive face? But no. Things never changed, and throughout the run I played my second major scene of the play (and it was a long scene) with my back squarely to the audience.

What Phyllida understood and I later came to learn was that it was almost like a film where the audience see things as Elizabeth does. They are behind the camera, so to speak and the camera is Elizabeth’s gaze. The arguments come in on her relentlessly and the audience feels the weight on her shoulders as if it were their own. All I did was listen and any reactions that flitted across my face were for my courtiers alone. My impenetrable back gave nothing away and the scene was all the more powerful for it. My face could not have done a better job, in fact it would have been a let-down. Phyllida saved me from that. I could trust my director because she knew how to make an image tell a story.

The Privy Counsellors, Mary Stuart by Friedrich Schiller, design Anthony Ward, Donmar Warehouse, 2005. Photo credit: Carmel Vargyas

Caption: The face my Counsellors saw but the audience never did, HW. Mary Stuart by Frederich Schiller, design by Anthony Ward, Donmar Warehouse, 2005. Photo credit: Carmel Vargyas

The Relationship with the Audience

I mentioned before that the magic created on stage is for the audience rather than us. Just as a pianist can’t get too involved with listening to themselves as they play but must send the music out and share it, actors who indulge too much in their own feelings, marvelling at how tragic they are being usually switch the audience’s emotions to “off”. The absence of a fourth wall forces us to look out to you in the audience. When my back is turned I can for a moment luxuriate in the same illusory world that you are seeing but for the most part the reality of my field of vision is 160 degrees auditorium and 20 degrees set. If you have ever been invited backstage after a play and stepped out on to the stage to see the actor’s point of view of the stalls, you will know what I am talking about.

Another little anecdote from drama school. We were in an improvisation class. The teacher set us up solo or with others, threw out a very brief suggestion of a situation and placed a piece of furniture or perhaps a prop in the space. You were not to think about it for long but jump in and run with whatever came into your head. Spontaneity was everything. I was given a stool, a small table and a piece of paper. I’m instantly in a prison cell on the eve of my execution. I am writing to my beloved and speaking aloud the words I am writing (as one never does in real life). I can’t remember anything of what I wrote/said but it was something like “My dearest Maximillian, the inevitable will happen at dawn tomorrow. Do not grieve for me, I pray. I have lived long enough and I now pay for my sins with a willing heart…. I can hear the first sweet birds heralding the dawn which is to be my last. I must put down my pen but I will whisper these last words “I love you” until my last breath is drawn. I whisper them to the walls of this cell, to the fetid air and..” (swivelling my chair round to face them) “..to the 24 or so students sitting watching me in the auditorium.”

The long delicious laugh I got from the group is why I remembered this impro. But now I can analyse it as a moment of irreverence, of breaking the almost holy contract between actor and audience. What I say and do in this imagined space is, for the time being, true. You, in the audience, willingly suspend your disbelief and see what we want you to see. I had summed up the paradox of my future working life albeit in a rather glib absurdist way.

The idea of prison triggers another memory. Back at the Donmar again with Phyllida Lloyd. It is the first day of the technical rehearsal of our all-female Julius Caesar set in a women’s prison. Bunnie Christie has done something extraordinary converting the entire auditorium and stage into a believable space within prison walls. Here there is no division between audience and performers because the audience will come into our prison space. We will all be wrapped in the same environment.

The illusion will begin in the foyer. Bags will be searched, exits will be barred by prison (theatre) staff. But for me the most transporting moment in the technical rehearsal came before I even hit the stage. We filed in to the wings in our regulation grey tracksuits and there, instead of the friendly opening on to the stage was a heavily locked grey-painted door with a little barred window in it. Only the guards (stage management) could unlock it. That piece of design-thinking gave me the last vital piece of inspiration I needed. Instead of an artiste hovering in the wings of a chi-chi Covent Garden theatre, I was an incarcerated woman who had been given a rare and precious license to perform.

Prisoner, Hannah, about to go on as Brutus in an all female Julius Cesar by William Shakespeare, design Bunny Christie, Donmar Warehouse 2012. Photo credit: Simon Annand.

The Last Image

To quote Peter Brook “A man walks across the empty space whilst someone else is watching him, and this is all that is needed for an act of theatre to be engaged”. So where does that leave the designer? All I have is my body, my face and my voice with which to convey some very complex ideas to a multi-headed audience. Brook’s example may invite them in, engage them, but how to keep them watching? How to take them with us through a roller coaster of events and emotions? We all need help from the designer to locate us, create a physical environment that will support and guide the audience’s experience. The designer can also create an atmosphere translated from the eye to the other senses, one that will linger in the memory longer than coherent thought

In the same way that a city’s streets, monuments and buildings outlive the many generations that pass through them, I would argue that the image of a play is what is left behind when every other memory has faded. People remember plays in their mind’s internal camera. “I will never forget the way she bent over the dying child” “That moment when he slid down the bannisters” If you were there on the night you might remember snatches of dialogue, the music of a line delivered, but the record of the performance for those who weren’t there lies usually in a description of a picture. A startling visual effect or extravagant piece of business is more easily pinned down in a review than a flicker of thought across a face.

Posters, glossy books of stills photographs are all that can be captured and taken away from a “you had to be there” event. The image is what you hang your memory on and it draws all behind it. The image sums up the play for posterity. In the beginning is the word but in the end is the image.